Appalachia Gets a Good Rap

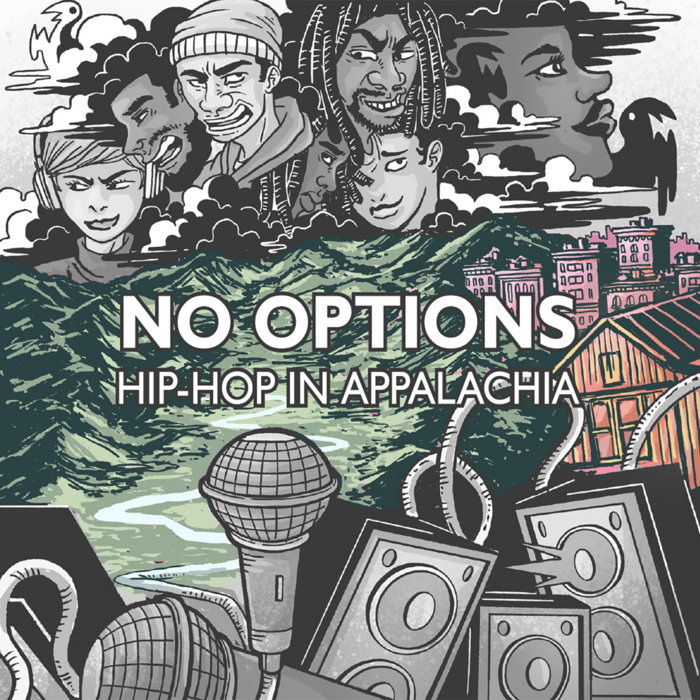

On the upcoming compilation album No Options, more than a dozen Appalachian hip-hop artists present a different side to an often misunderstood, oversimplified region.

Monstalung doesn’t fit the usual stereotype of a hip-hop artist.

That’s in part because of his childhood surroundings. Far from being grounded in a single city, narrating a hyper-localized existence on a Rosecrans Avenue or Fulton Street, he spent his adolescence in a state of perpetual motion — moving all over the country with his parents in support of their arts careers, and later, in pursuit of his own.

It’s also because of the place where he ended up. Although the veteran emcee and producer (born Eric Jordan) spent many years working in major hip-hop hubs like Atlanta and Chicago, his story revolves around the comparatively humble Morgantown, West Virginia, where he settled in 1999 to help establish the local arts scene that exists there today.

Prior to that, his name could be found on the same bills as national acts like Lil Wayne, Trina, Lil Jon, and Slick Rick, and at one point in the 1990s, he was even courted by the Chicago indie label Fathead Records. But his was never the straightforward, easily-marketable “rags-to-riches” major label breakout story. In the conventionally city-centric rubric through which hip-hop is often understood, he didn’t tick any of the usual boxes.

It’s that distance from the traditional rap trajectory that makes Monstalung a particularly appropriate bookending artist for No Options, set to be released by Kentucky’s June Appal Recordings this Friday. The label’s first-ever hip-hop album examines one of the remaining unsung regions within the genre’s ever-expanding practice: the verdant hills and small manufacturing towns of Appalachia.

Across 24 tracks, No Options serves as an anthology of artists whose stories contain echoes of Monstalung’s. Capturing the disparate but interconnected nature of America’s oldest mountain range, with contributions from Tennessee to Virginia to North Carolina, the project challenges the reductive understanding of Appalachian music as solely rooted in the twanging strings of folk and bluegrass, and solely the domain of white, working-class musicians.

It’s a necessary reminder of the significance of Black musical history in a region often stereotyped as white. After all, this is the Appalachia that hosted Black freedom communities, an abundance of Black mine workers, and poetic and musical traditions that poet Frank X. Walker once coined as “Affrilachian.”

“For most of American history, the region was just ignored. It was an extractive region… able to produce things that the rest of America could consume,” says the album’s executive producer, Jomo “JK” Turner. “But at the same time, the people who were producing these things were grossly overlooked.”

Turner’s life itself is deeply intertwined with the Black cultural contributions in Appalachia: his grandfather was a coal miner in Lynch, KY, and his father, Dr. William Turner, is one of the eminent scholars of Black life in the region.

In 2022, bolstered by a grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission, Dr. Turner and Eastern Tennessee State ethnomusicologist Dr. Ted Olson set out to produce an album of Black Appalachian art that represented the new musical pathways of the region. The two professors, now in their 70s, knew they wanted to examine hip-hop’s presence in the region, but also knew they needed help addressing a form that they knew relatively little about. Serendipitously, JK was born just a day before hip-hop itself, on August 10th, 1973. As a lifelong hip-hop fan, he had dabbled in the art form himself, freestyling and making beats for fun.

Once JK took on the project as executive producer, he started reaching out to Olson’s extensive network and got connected with Monstalung, who Olson calls “the godfather of Appalachian rap.” He made contact with artists in eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, West Virginia, and beyond, eventually working with June Appal Recordings to sift through the submissions and curate the final cut throughout 2023.

The end result is a vibrant mosaic of Black musical traditions in and through Appalachia. The hook of the first track “I Will Not Lose” — featuring lyricism from Jumbo Green and production from Monstalung — represents the tragicomic highs and lows of the region’s history: “Jack and Jill went up the hill/ Jack wasn’t strapped so Jack got killed/ Jill turnt out, now she’s on them pills/ sounds fucked up, but it’s real.”

Sonically, No Options encapsulates the kaleidoscopic Black musical traditions that emerged from the migratory patterns of the 20th century: Deep Jackson’s “West Virginia Reign” features a chopped soul sample that echoes hip-hop’s golden age; Black Atticus and Kelle Jolly’s “Me and Mines” reflects on intimate love over a blowing tenor sax and wandering upright bassline; and Abderdeen, NC’s Jetpack John$on — one of two North Carolina artists featured on the album — brings drill to the country with the raucous contribution “Don’t Get Hit.” There’s even a Shaboozey-esque country trap anthem, courtesy of Joshua Outsey’s “Virginia Is For Lovers.”

More important than its sound, though, may be the visibility that this project brings to the diversity of the region. “It lets kids who have no voice know that they can have a voice,” says Monstalung. “If they can just get that out and see that — and not just kids — if anybody in any age range can see, hey, there's people who live in a similar place like me that are doing music and have an outlet.”

Even for many of the artists featured, the project itself was an important illustration of Monstalung’s point. Ced Bankz, a Winston-Salem emcee who contributed “Die Alone” and “Let Em Know,” said of his initial connection with Turner: “Will reached out to me and asked to send them some songs, and the rest was history.”

Indeed, it was history for Bankz. The project is one of his first placements on a full-length album, and this is the first time he’s been interviewed by a publication. For many of the artists on the album like Bankz, No Options gave them a chance to represent their work in a media landscape that might otherwise pass over them completely.

The story of hip-hop is often told as the afterlife of the Great Migration, the result of millions of southern Black Americans relocating to urban centers in the North, in search of the safety and economic security of — as Isabel Wilkerson famously put it — the warmth of other suns. Once the manufacturing jobs dried up during the rise of the global economy in the 50s and 60s, Black enclaves in these cities suffered from a lack of opportunity and malignant municipal neglect. Hip-hop was born as the sound of this urban struggle, and, as a result, it became the sound of the city.

Like the greater Applachian hip-hop culture it pays tribute to, No Options presents a challenge to this oversimplified tale. What we hear isn’t just the sound of people stopping and settling along the way of the Great Migration, true as that may be. It’s also the sound of the extraction of those rural resources that powered urban manufacturing jobs, the sound of families moving to and from remote regions in search of opportunity, and the sound of the digital age bridging musical divides and widening economic ones.

In short, it’s the sound of how hip-hop has always been in motion beyond the confines of the city, moving as people do. No Options helps us to hear how hip-hop, now in its 51st year, is continuing to grow — from the street corner, all the way to the holler.

Tyler Bunzey is an educator and music journalist who's covered queer pop, R&B, and more for places like CLTure and QC Nerve. He runs the Cultural Studies major program for Johnson C. Smith University. He can be found on Twitter at @t_bunzey.

Christian Arnder is an illustrator and graphic designer based in Winston-Salem, NC. He’s been working with bands, brands, design firms and publications for 10 years. You can see his work, and his running memes, at @christianarnder.